The “will of the people” is a particularly insidious concept; the phrase is trotted out to end arguments using an argumentum ad populum fallacy, and for certain people to justify things to themselves (if not others).

I’ve previously noted my dislike of the false simplicity of labels: seeing ‘one people’ instead of ‘many peoples’; or mistaking those who shout most frequently or the loudest as being representative of an entire group.

Such thinking leads to simple-minded views, that all ‘right-wingers’ must be Nazi racists hypersensitive to encroachments on their way of life, that all left-wingers must be communist rioters hypersensitive to speech they don’t like, that all Christians must sex-fearing women-haters, or that all Muslims must support terrorism.

Simplistic worldviews – essentially one of goodies and baddies – can only see people as supporters or opponents, with strict standards of ideological purity (among those who fail these standards are the ‘cucks’ and ‘gender traitors’).

When one is convinced that one is working for the betterment of the world (whether through religious, political, or legal means), it’s easier to discount the views of others – who, by definition are seen to be working against the betterment of the world and must be stopped – and in extreme cases, it becomes easier to justify violence against these ideological opponents. If things get to this stage, it’s a lot harder to get everyone to talk to each other again.

Inquisitions, jihads, pogroms, revolutions, bombings and genocides sprout from similar self-righteous seeds as riots, violent campaign rallies, the silencing of dissent, or claims of lawbreaking as a justification for assault (it’s happened with jaywalking and refusing to comply with airport police) or murder (if one has brown skin).

*

How to stop things getting that far?

To begin with, we need to drop absolutism from political discourse.

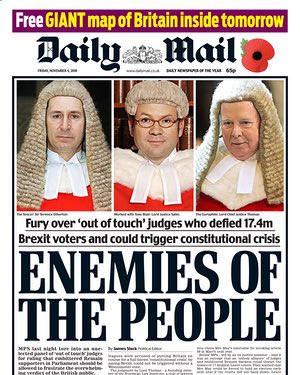

When Nigel Farage described Brexit as “a victory for real people”, he immediately cast half of those who voted as ‘non-people’ whose views could be ignored (as Prime Minister Theresa May has subsequently done), and any opponents as ‘enemies of the people’, as the Daily Mail described three senior judges in a headline with disturbing parallels to 1930s Germany, as many of its headlines tend to (although it must be noted that the details in the two stories differ substantially). One might ask who benefits from such rhetoric, and whether they’re well-disposed to ‘the people’.

Similar unfortunate discourse came in the wake of the Scottish Independence referendum – the outcome was said to be “The settled will of the Scottish people” – which, even as a ‘No’ voter, I thought was simply untrue; the 45%-55% split indicated to me that the matter was far from resolved and that the views of the 45% (which included majorities in two whole cities) should not be ignored. But ignored they were, and the SNP soon came to dominate Scottish politics at the following election. In the wake of Brexit, a second referendum is awaited.

A related problem comes from those electoral systems where the outcome does not reflect the turnout or proportions of voters for each candidate or party – what counts as a mandate?

Assuming a functioning, uncorrupted democracy – preferably one that operates with some form of proportional representation – I’d be tempted to say that only a simple majority of the electorate can provide a mandate. The victories of the Conservatives in 2015, Brexit, and President Trump in 2016 owe more to large enough minorities of the electorate to claim victory – and certainly do not reflect some nebulous ‘will of the people’.

A tyranny of the majority is bad enough, but tyrannies of self-righteous minorities claiming to represent a whole nation – essentially, mob rule – do not have a glorious history, whether one looks at The Terror in France, Brownshirts in Germany, or comparatively powerless movements claiming to represent moral majorities in more recent times.

Mobbing and bullying in the belief that you’re doing it to make the world a better place is an ugly practice. Sadly, it’s one which shows no sign of being eradicated, and its resurgence, alongside that of 21st-century caudillos from Trump to Putin to Erdogan, is a cause for despair.

At time of writing it is only a day since Prime Minister May called a snap UK election. Between that and her tabloid-friendly ‘will of the people’ rhetoric, it looks like she wishes to set herself up as a mujer caudillo, untroubled by opposition (or anyone who might complicate things).

It’s bad enough reading about this happening in other countries. When it happens in one’s own, and the appalling precedent it sets, it leaves a profound sense of foreboding for the future.

The “people” thing is weird and something I have a lot of uneasy but incoherent thoughts on, mostly influenced by my time in Germany. Obviously the equivalent German term, “Volk”, was heavily used by both the Nazis and the Communists, so both dictatorial regimes from either end of the political spectrum. The protesters against the East German regime reclaimed it, chanting “Wir sind das Volk!”, so there’s that association with it as well. Even so, you don’t hear the term that often now.

The Reichstag Building has an inscription above one of the entrances: “Dem Deutschen Volke”, To the German People. There’s an artwork by Hans Haacke in one of the courtyards called “Der Bevölkerung”, To the Population. He was making a point, of course, about the problems with the term “the people” (and how limited “the German people” is when parliament has to represent everyone in the country). It was so controversial that parliament ended up having a plenary vote on whether to go ahead with it. It was a very narrow decision in favour. Someday I’ll have to go back and read the transcript of the debate properly (it was before my time there), as it would be interesting to see the arguments in more depth. In any case, I’ve always considered it a really interesting piece of art because it deals with that issue. It’s the first thing I think of whenever the subject of “the people” comes up.

(Oh, and I agree with you on the political side of things too. But I’m still at the alcohol-swilling stage of depression on that front, so I’ll leave it at that, haha.)

Cheers Emma!

For me, talk of “the people” is a giveaway that you’re either dealing with a tyrant or a wannabe-tyrant; no good will come of it. I don’t know if it’s my imagination, but the phrase seems to crop up more frequently than it used to. When I was a kid, it was the sort of phrase that cropped up in Cold War thrillers and historical dramas, uttered by the devious baddies. Now it’s part of everyday politics! (What does that tell me?!)

The German distinction between ‘the folk’ and ‘the people’ crops up in “The Pursuit Of Glory: Europe 1648-1815” by Tim Blanning – if anything, it shows that the problems we have now are problems that have always been there. (I did a summary here: https://observaterry.wordpress.com/2016/12/27/folks-needs-and-peoples-wants/ )

Pingback: Lying Cu*ts | Observaterry·